‘How do I run faster?’

This is THE question. The answer is different for everyone. Some people need more miles; some less; some need speed; some need strength. Some need to get out of their head and have fun.

Here’s what I needed:

The world is always speaking to us; telling us not what we want, but exactly what we need to hear. Over and again. Unfortunately I’ve often been too stubborn to always hear it clearly. In hindsight I can now not only see the message, but also that it has been consistent. What then does the world share with me when I am humble enough to listen?

That I am not special.

There are, undoubtedly, special people out there. People who have been genetically blessed to sing, dance, play, think, act, run. Think of the LeBron James, Tom Hanks, Bill Gates, Shalane Flanagans and Michael Jacksons of the world.

I wonder what the world tells them.

I am not one of those people.

I’m guessing you aren’t either; and here we are.

Acceptance

It took some time to accept it but I’ve finally heard you loud and clear World. Whatever I get I have to work for. I’m not special. Not even when it comes to running.

My emergence as a fast runner didn’t happen miraculously. I didn’t outrun older bullies or win my first race. Surprisingly, there was no amazing performance that said ‘Watch out world! We have a runner here’. I have scattered memories of placing well in the St. Theclas fun run as a kid; of winning the timed mile in gym when no one else was racing. The sudden emergence of a hidden talent only happens to special people or in the movies; we’ve already established that is not me. My story is less entertaining but, I think you’ll find, just as valuable.

I’m a Born Runner

Though my years of running and competing reinforced that I’m not special, I have possessed one thing that can’t be taught: I’m a born runner. That doesn’t mean I am blessed with an elite runner’s body: I’m not. I’m too tall and too muscular. What it means is that I’ve always wanted to run, and to run faster. I’ve always loved it. When I was 6 or 7 I would run around my neighborhood (+-1 mile) just to see if I could do it. Somewhere in the depths of my Father’s basement you may find my 3rd grade daily journal (Ms. Kirkpatrick’s class) where one day I wrote an entry about how much I enjoyed distance running. Some people run to run, some people run because they’re pretty good at it. I ran/run because on a fundamental level it’s always been part of who I am.

The race doesn’t always go to the swift

Fast runner or slow, remember this quote: ‘ the race doesn’t always go to the swift, but to those who keep on running.’ That quote explains my success as a runner, and moreover as a person. I just keep running.

First Steps

My first brush with running fame came when I broke the indoor mile record for my elementary school. 36 laps around the gym. Think about that for a moment. 36 laps to a mile. A gym so small you had to leave the room to change your mind.

I’d run pretty well in the timed mile a few weeks prior and thought my daily paper route constituted a training regimen. So I set up an attempt at the school record with my gym teacher Mr. Levangie.

I remember 4 things:

- being excused from watching Johnny Tremaine on a Friday to make my record attempt.

- Sprinting lap 36 while Mr. Levangie yelled out ‘finish strong!’

- Returning to the classroom, holding up one index finger and nodding my head as a way of telling my friend Jason Trotta I had done it.

- The final memory: Pain. Uncontrollable coughing and wheezing for the remainder of the day.

My reward for setting the record: burning lungs and track hack. To this day I can still feel how badly it hurt afterward. Every single breath was agony, though I’m not complaining.

All in all the price for being the fastest distance runner in school was easy. A little bit of talent (nothing special) and the willingness to suffer for 36 laps. Running, on the whole, is hard, boring work. Most kids don’t want anything to do with that. I did. I’m a born runner.

The Running Man in 6th grade

That record fell a year later to a kid named Michael Duclos. I didn’t have a chance to retake it because I’d switched schools. I was now the youngest member of varsity track at Thayer Academy as a 6th grader, running the two mile in 12 flat. That was about :20 per mile faster than my record setting 1 mile performance the year before (and faster than Mike’s new record- Ha!). That’s the benefit of running 4 laps to a mile, instead of 36.

I LOVED being on that team. The workouts left me bone tired. My legs were eternally sore. I felt like puking before every race. Somehow, even though I was only 12, I earned a varsity letter. Our distance stud, Brian Wilson, dropped out of a race with a lap to go. Instead of coming in 4th out of 7 I squeaked out a point for coming in 3rd. The world was telling me something that even I wasn’t too deaf to hear:

You belong here.

Changes

I dropped my baby fat, leaned up and got really fast that spring; not only over 2 miles but also in sprints. I was never the fastest guy in Soccer or basketball practice, but after months of 200/400 meter repeats and ladder workouts I was easily winning wind sprints at the end of practice. That spring I won the St. Theclas 1 mile fun run, out-sprinting 2 kids from Hanover for my first win.

My reward for winning my first big race: vomit. I vomited raisin bran all over the finish line. The crowd went from elated cheering to disgust in a heartbeat. An important lesson: never eat dairy before racing.

The price to win my first race was steeper. I trained all spring and ran tons of intervals and races. I suffered stiff hamstrings, and legs that burned with lactic acid. In spite of all of that I’d gladly pay the price again.

True Love

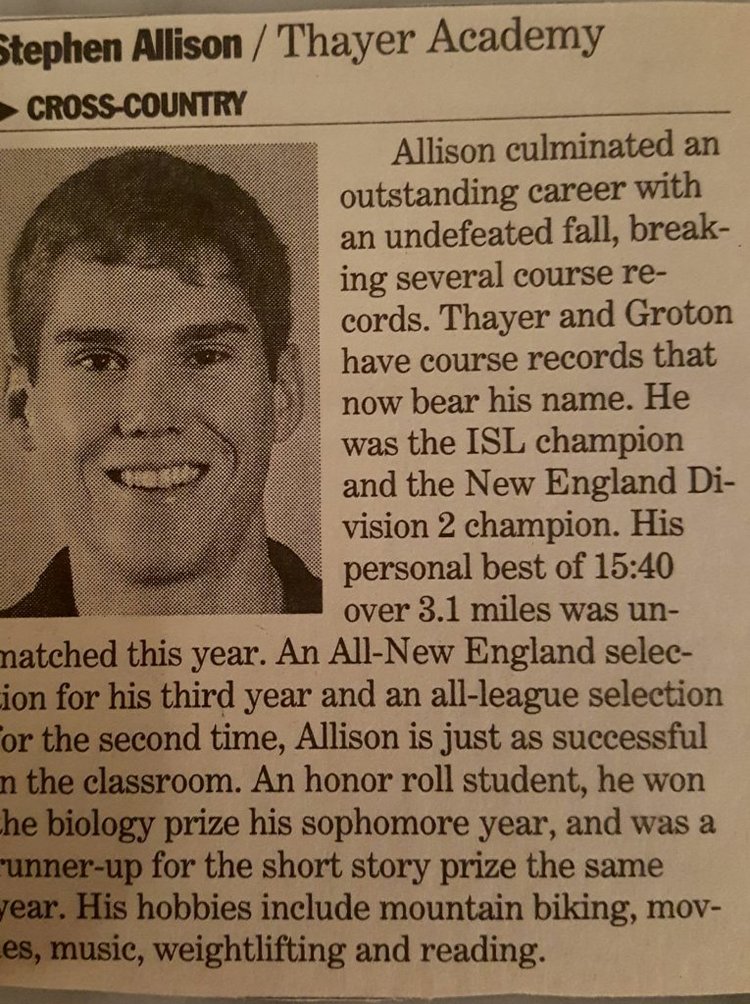

I ran track every spring, improving modestly. Then my sophomore year when I fell in love with Cross Country. Track is fine; however running lap after lap during a cold, damp New England Spring is decidedly less fun than running through autumn woods with Harold Hatch as your coach. Everyone on earth should fall in love with someone/something the way I fell for Cross Country. I can vividly recall how amazing my first race felt; how fun my coaches were; how much I loved my team and our weekly team dinners and road trips.

The first season showed potential. I broke 17 minutes for 5k and made the All New England prep team. Pretty good, but not good enough. I was in love. I needed to be special. That wasn’t happening by accident.

I laid out my athletic future.

- Win my league meet

- Set my school cross country record

- Run in college.

Interesting?

I would tell my goals to anyone who would listen. I was winning the league and setting the record. The school paper quoted me saying as much my sophomore year. A young Babe Ruth calling his shot. I even told my coach. A week later, during the fall awards banquet he had this to say:

‘Steve is (dramatic pause) an interesting kid. In order to win he has to outwork everyone.’

I’m interesting? And I have to out work everyone? I’m not special?

Best thing he could have said. Unfortunately I had no idea what outworking everyone meant yet.

Success, you may have learned, is never a straight line. My junior year summer I stepped up my training. The previous years “training” consisted of daily mountain bike trips. This summer I’d actually run. I ignored my coach’s training plan and just went out for 4 or 5 jogs every week; the longest being about 7 miles, thinking this constituted enough training for me to win the league next year. The world told me every chance that I wasn’t special; perhaps I hadn’t heard clearly enough.

Failure is the best Teacher

My training was haphazard and disorganized and, as a result, my improvement was tepid. I made all league (top 5) and ran faster, but not by much. I hardly improved on my home course (still languishing a full minute behind the school record). No college coaches were knocking my door down just yet. If I was going to make good on my promise to win then something was gonna have to happen. Like Einstein said

‘Everything is energy and that’s all there is to it. Match the frequency of the reality you want and you cannot help but get that reality. It can be no other way. This is not philosophy. This is physics.’

This is an intellectual way of saying that to run with the big boys you’ve got to train like them. To run faster I had to approach training at a different frequency/energy level. I wasn’t training to set an elementary school record, or win a local fun run. There were other kids who loved running just as much and I was not special.

What did outworking everyone mean?

The price is steeper

My lack of a major breakthrough was partially due to me not training hard enough the previous summer, and partially because I was a late bloomer. I was tall, skinny, and not too muscular. That summer I filled out a bit, and even began shaving (two, sometimes three times a month!). I was seeing results from the weight room for the first time. My body was changing.

Goal check.

On the positive side I was the second fastest underclassman in the league, and I’d beaten the other kid before. I could win the league meet.

On the negative side the school record felt out of reach. I focused on getting :30 faster instead. Watch a friend walk away for :30 seconds and they’ll become a dot. Now imagine they’re running. That’s the distance I had to cover. 16:10 seemed unspeakably fast, but I lied to myself every day and said I could do it.

If I ran that fast maybe I could run in college.

Build your Base

That summer the towns of Pembroke and Duxbury cleaned up the edges of route 53. No more pot holes, broken crags of concrete, overgrown edges, or shards of broken glass. They manicured that roadside into a dirt berm that was packed hard enough that I wouldn’t lose speed running on it, but soft enough to save me from smashing my shins and tendons to bits while upping mileage. Looking back, it was fate. That was the summer I learned to run fast and this was the perfect surface to do it on.

I piled on the miles. This time I memorized the simple running plan Coach Hatch had tucked into the back page of an orange fall Cross Country packet. Increase your mileage by no more than 10% a week, make sure you ran long once a week (20-25% of weeks miles in one shot), get that long run up over 10 miles, and in August start adding a weekly monster workout. Something like 4 x 1 mile repeats.

Build a big base. Whittle it down to a sharpened peak by November. Simple works.

Stick to the plan

I ran that long stretch of rt 53 so often I can remember every pot hole, hill, intersection, driveway and store along the way. I ran it on 90 degree days, and even a couple 100 degree days. Neighbors and friends would constantly greet me with ‘I saw you running.’

I ran a specially designed 12 mile course twice a week because it felt good.

August came and I started my Monster workouts. I drove to the track behind Silver Lake high school and ran a timed mile in 5:15. It felt easy. I rested and then ran another in 5:18. Then 5:25, then 5:28.

‘Maybe I can run in college,’ I thought as I walked back to the car. It was one thing to say I would run in college, now I was believing. I hope that you, dear reader, feel that same sense of accomplishment and hope that I got from that workout.

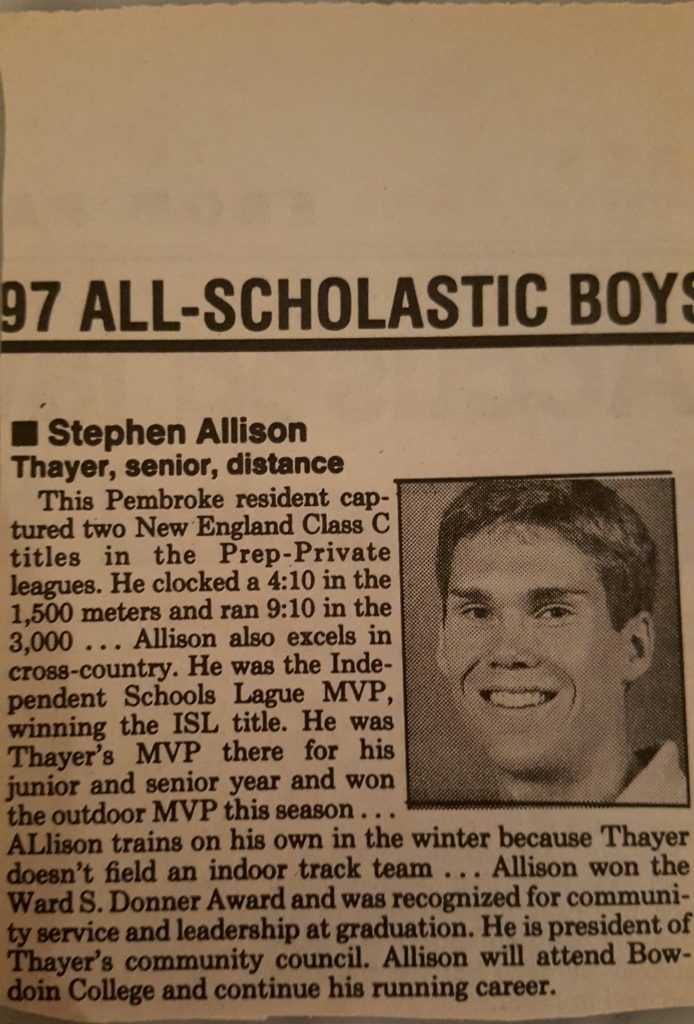

The Dream Season

That season was magic. The training/maturity catapulted me into a different league. The highlights kept coming and the more I ran, the more I believed. I placed 5th in an early all state meet (thought I had it with a mile left); accidentally ran a 4:20 (PR) mile in the first mile of a 5k (whoops); won my league title; and on a perfect October day I scored a huge PR on the home course, running a school record 15:43 (almost a full minute faster). Didn’t see that coming.

Years later I realize that I’d unwittingly spoken goals into existence; That’s proven more powerful than anything I learned in the classroom.

My Coach

You don’t become your fastest self without someone dragging some of it out of you. Harold Hatch was my Coach. He was steady, fun, and had command of of training and programming. Importantly, we discovered he’d won some big races himself, so he was authentic. We believed in him.

He was a born runner.

Years later dozens of loving students, family and appreciative parents attended his retirement party. We went around the room sharing our stories about what he meant to us. Though on the surface he was a math teacher and Cross Country/track coach it occured that he was the richest man I’d ever met.

That night I shared what he’d meant to me personally, but I was young and inarticulate. Whatever I said was forgettable. I wish I had a do over. I’d remind him of how before our biggest meet he’d strategized with every runner, from 7 man on down. He told them what kind of race they’d need for us to win, and offer some insight. Finally he came to me. he stared at me. Silent. Then, after what seemed an eternity he pointed his index finger at me and said nothing. Another minute went by. Then he lifted his finger, pointing it upwards.

I won the race by 11 seconds.

As I finished that story I’d point at him, and then upward.

I’m not special- I just work harder

The Boston Globe and Patriot Ledger were my local newspapers growing up. Every season they’d choose their all scholastic athletes in every sport. I dreamed one day I’d be good enough at something to be selected, but realistically, I never thought it would be me. I’m not special.

I looked at those kids year after year and thoght these guys/girls were heroes. I’m not ashamed to admit that I struggl with self esteem. All scholastic made me feel like somebody. Still does actually.

The price for being a high school star was steeper. 40 miles a week, harder workouts, running in all weather, filling out a training log and finding the right mentor.

Years later when Coach Hatch, was inducted into our High school athletic hall of fame with his son Mark (3 time league champ), someone passed me a sheet of bright orange paper. ‘Remember this?’ On it was Coach Hatch’s summer training plan. Holding it in my hands I was overcome. I literally burst into tears at the sight of it. Why? Because I have what you can’t teach. I’m a born runner. We define ourselves by how we run.

That sheet of orange paper changed the definition.

I enrolled at Bowdoin College in the fall. I was in the top 10% of my graduating class GPA, captain of two teams, president of the student council. In the words of Kanye West ‘Ya can’t tell me nothin’.

I thought I was hot shit that fall. I thought maybe I was special.

I’d quickly discover how wrong I was.

There I was, sitting in an auditorium with my new classmates during freshmen orientation and the dean was giving us the rundown on our class.

- 90% of you were in the top 10% of your graduating class.

- 80% of you were a sports captain.

- 60% of you were involved in student government.

There were three other classes full of similar students enrolled already.

Translation- you’re not special.

The same lesson came in running. You think you’re hot stuff because you were all league this, or all state that? Well, get on the start line of any collegiate race and look to your left and right. Everybody on that line with you was all state, all league, all world. Every one.

My freshman year I got demolished. Sophomore year I trained I stepped up my training. Back to the drawing board. First order of business is we’re going to outwork everyone. I ran hard every day, took NO days off and promptly ran myself into the ground. Runners knee, then shin splints, then a sprained ankle, then a cortisone shot, then 6 months of no running.

Maybe I was just a good high school runner. Maybe I couldn’t outwork everyone at this level. I thought about quitting.

Nah. I have what you can’t teach: I’m a born runner.

The race doesn’t always go to the swift, so I kept on running.

Injured

Serious injury happens to every runner. If you can push through them you can truly say that you love running.

Training more with a vague plan wasn’t enough to win in college. So junior year I smartly, seriously, and cautiously upped my mileage; running more than ever but taking care to schedule in rest and stretch a little.

Match the frequency of the reality you want.

I read a bunch of books about training, then took 6 months to heal my injuries and build up mileage the right way. I got a job at Marathon Sports where I befriended a slew of older runners who were much, much faster. It is a drastic understatement to say I learned a lot from them- more than I could share here. I’m eternally grateful to Ashley Johnson and Dave Menoski for their mentorship.

The main thing they taught me

If you’re looking to improve and you’re the fastest person on your team or in your group, find a new team/group.

That fall I returned to college and dropped over 100 seconds off my best freshman time. Over the next year and a half I went from being so injured I couldn’t run down the street to conference champion and All American.

I won the Hingham 4th of July road race (over 4,000 people) while training through it.

I was named Outstanding Athlete of my graduating class. Joan Benoit Samuelson gave me the award (Joan is special and outworks everyone. I just outwork most people).

The price to be a collegiate star was full immersion into running as an identity. Just running more, though crucial, will only get you so far (fast). To get better at this level you have to be more disciplined, more intelligent, you’ve got to listen to your body, and train/learn from those who are better than you. You have to put in 70 to 100 miles a week for most of the year. Run in the rain, blizzards, extreme heat.

It’s more fun than it sounds.

If your ego can’t take losing, or failing then you’re running to reaffirm your idea of how good you are, not running to improve.

You won’t reach your potential without getting your ass kicked.

You’re not special.

I think you have to get seriously hurt at least once to find out if you love it enough to come back. It’s the Running God’s way of making sure you want it. How many faster, more gifted runners did I outlast because they were only good when it was easy?

The race doesn’t always go to the swift.

So you want to get fast? You don’t have to be especially talented. Hell, all it takes is one thing:

Decide that you’re a born runner.

Call yourself a runner. Think about it every day. Run more miles than ever; run them faster than you thought you could; run with people who are better than you; get your ass kicked; learn in defeat; return the favor; read the books; get hurt; come back; learn from mistakes; puke at the finish line; bake on summer long runs; freeze on winter ones.

Keep on running.

Do it long enough and eventually the world will confirm it.

That (plus more) is the price you gotta pay to get fast.

It’s worth every cent.